Curriculum Guidelines

This guide provides direction around the key curriculum components needed to provide standardized training. Each curriculum component is defined and examples are provided. This document also includes links to online resources and examples.

Table of Contents

Introduction

The Alliance for Professional Development, Training, and Caregiver Excellence (Alliance) has developed the Statewide Training Curriculum Development Guidelines (guide) as a tool that will provide recommendations for the curriculum development process. This guide will help ensure statewide consistency and ease of design and delivery of all trainings provided by the Alliance. The Alliance has a vast pool of subject matter expert (SME) trainers and curriculum developers. This guide will provide recommendations for the curriculum development process, along with supplemental components outlined.

The Alliance provides learning opportunities created to optimize knowledge, values, and skill acquisition for adult learners. These opportunities build values consistent with excellent practice; individual, family and organizational well-being; knowledge of practice standards and policies; and the acquisition of skills to improve outcomes for the children, families, and communities of Washington State. The Alliance’s course offerings are generally organized into three different categories.

Foundational learning is designed to prepare learners with the basic knowledge, skills, and understanding of their roles. These trainings enable these individuals to meet standards for their roles and they help meet mandatory on-going professional development requirements.

In general, foundational learning comprises cohesive developmental curricula in which knowledge and values are broadened and deepened. Learners are introduced to the skills necessary to engage in the responsibilities required of their role. Foundational learning provides participants with blended learning opportunities, including classroom instruction, reflective/field activities, and skill-based practice opportunities. These learning opportunities are active, interactive, and collaborative and they support the early transfer of learning from classroom-based instruction to direct application of skills.

Continued learning allows for a scaffolding approach that provides a deeper dive into more specific topics. These trainings can include mandatory trainings and optional trainings that enhance learners’ understanding of their role(s).

Continued learning opportunities comprise cohesive developmental curricula in which knowledge is revisited to deepen values and increase skills. Continued learning provides participants with blended learning opportunities, including classroom instruction, reflective/field activities, and skill-based practice. These continued learning opportunities are active, interactive, and collaborative.

Supervision and Leadership training and development enhances the ability of supervisors and managers to initiate and support organizational transformations that lead to improved outcomes for children, families, and communities.

Coaching for skill development is another category offered that supports the transfer of learning from classroom-based instruction to the direct application of skills, focusing on collaboration, mentorship, skill-building and self-efficacy. This coaching aims to reduce trauma response through education on positive regard, cultural humility, and strengths-based practice. Sessions are individualized to the learner and can occur virtually or in-person.

Trainers and trainees will benefit from consistently organized and formatted Facilitator and Participant Guides and the ability to easily locate resources and supplemental handouts and information. A standardized format for designing and developing curriculum will enable the Alliance to develop, resource, and evaluate in a consistent manner that will improve reporting to the federal government. The intended use of this guide is to serve as a resource to curriculum development teams, curriculum developers, and those who deliver training and coaching on behalf of the Alliance who have training needs. Resources are provided to guide curriculum development with attention to adult learning theory, best practices in facilitation, and transfer of learning. Within the guide, curriculum development processes are outlined. Within the Appendix section, resources are provided to guide curriculum development and to guide facilitation of training delivery.

Curriculum Development and Facilitation Framework

- To ensure consistency of curriculum development across curricula for the Alliance, the Continuous Quality Improvement (CQI) workgroup serves as the guiding workgroup to discuss, analyze, forecast, and plan for training to support the needs of training partners. This includes the identification of training needs, and implementation of new mandates and initiatives. The workgroup will:

- Work with partners to define training to meet the needs of the identified target audience

- Strategize and plan methods to support the training partner in delivering

- Review and approve recommendations for initial and ongoing training(s) to meet the training partners identified outcomes

- Act as SMEs in the curriculum development, design, and delivery and assist in providing feedback on recommended upgrades or revision to the curriculum as appropriate to meet the training partners desired outcomes

- Strategize and plan for implementation to support fidelity in delivery of training as well as application in the field of the target audience

When partners are prepared to discuss training needs with the workgroup, the following information should be provided for planning purposes:

A. Brief introduction and background of the training topic

B. Requirements for and objectives of the training:

- Is this a mandated training?

- Is this a result of legislation/litigation?

- Who is the target audience?

- Desired outcomes.

C. Mandated for all or made available to all

- What is the intent of the training?

- Is this an evolving practice that would require frequent and ongoing revision?

D. Funding availability and limitations

- Is this a funded mandate? What is the funding source?

- What are restrictions to the funding source?

- Are there reporting requirements?

E. Timeline for deliverables

- When does the training need to be available?

- Are the deadlines flexible?

- Is the scope of the project flexible?

- How often does the training need to occur?

F. Available expertise and resources

- Is there an identified SME?

- Are there workforce development tools and strategies that reinforce training and practice?

- Does curriculum already exist?

G. See Training Activities Charter for the process for engaging stakeholder groups to be included in the vetting of the curriculum.

H. Entity that is best able to and available to deliver the training

- In-house trainers or contracted trainers that need to be identified and developed?

- Will the training be delivered regionally, or should it be centralized?

- What is the best style of delivery, i.e., classroom, coaching, learning collaborative, conference?

- What is the best modality for delivery, i.e., in-person, toolkit, video, eLearning, hybrid?

I. Create an action plan based on the workgroup discussion:

- If the plan involves entities outside the Statewide Training System, a contract with the vendor will need to be implemented.

Criteria to Consider for Curriculum Development

Every funding source has requirements regarding the intended audience and the training topic. A vendor with an existing contract may be used if the contract includes the same funding source that will be used to develop the curriculum. Adding funding to an existing contract, or creating a new contract, will affect the timeline for curriculum development.

Ensure sufficient funding for all deliverables necessary for the creation, vetting, piloting, and revision of curriculum. Because curriculum demands are often underfunded, look for vendors that have funding available from another project to offset the costs.

Curriculum needs may come with short timelines for creation and implementation. Determine what Alliance curriculum staff is best able to accommodate short-term deadline demands. This is done primarily with internal Alliance staff, but at times may be done through consideration of an external vendor. If an external vender is needed, identify which vendor is best able to accommodate short-term and long-term deadline demands. This may be done through consideration of the vendor’s history performing similar deliverables or related experience in the topic area.

Development of high-quality curriculum requires exceptional proficiency in the training topic itself and calls for expertise in the principles of adult learning theory, curriculum writing, implementation, and knowledge of the child welfare system. The Alliance recognizes and acknowledges the limitations of internal expertise and continually strives to bring in the lived experience of those most deeply affected by the injustices we hope to reverse into our practice. It is essential to select subject matter expertise in the field and to situate specific course material within the broader context of the child welfare system.

Because curriculum needs come with short timelines and quick turnaround times, it is necessary to evaluate the vendor’s workload to determine whether they have the capacity to increase their deliverables in a short period of time, should the need arise. Delays and/or failure to meet contracted deadlines may result in penalties to the vendor.

It is important to determine the timeliest approach to developing curriculum with consideration for quality. A method to identify, review, and leverage any existing resources shall be developed. Consider currently resourced SMEs – on staff or under contract – who can meet deliverable needs.

It is important to determine the most cost-effective and timely approach to developing curriculum with consideration for quality. A method to identify, review, and leverage any existing resources shall be developed. Consider currently resourced SMEs—on staff or under contract—who can meet deliverable needs.

It is critical that all curricula and associated materials meet the standards set by The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA), Section 508, specifically, WCAG 2.1, Level AA conformance.

For the development and revision of eLearnings in our curricula, use the eLearning Accessibility Checklist as your guide to accessibility requirements.

The Alliance curriculum is inclusive of stakeholder engagement. Individuals’ strengths and experiences are recognized and built upon. Empowerment, voice, and choice of children, youth, and families with lived experience are supported in shared decision-making and goal setting to determine the plan of action they need to heal and move forward. This is a parallel process, as staff need to feel safe.

The organization actively moves past cultural stereotypes and biases; leverages the healing value of traditional cultural connections; incorporates policies, protocol, and processes that are responsive to the racial, ethnic, and cultural needs of individuals served; and recognizes and addresses historical trauma.

The importance of collaboration and mutuality is placed on partnering and the leveling of power differences between staff and clients and among organizational staff, demonstrating that healing happens in relationships and in the meaningful sharing of power and decision-making.

The evaluation team partners with the Alliance throughout curriculum development, implementation, and revisions with timely data collection, analysis, and reporting. One way that Partners for Children (P4C) evaluation can support excellence in curriculum development is through pilot evaluation. During the pilot implementation of a course, observation data and feedback from instructors and learners support assessment of pacing, feasibility, logistics, appropriate level of learning activities, support needs of instructors, learner engagement and achievement of intended learning objectives, and perceived needs. P4C representative will join with the curriculum workgroup to propose evaluation methods and with group consensus develop implementation plans. The group will convene to review and recommend modifications and improvements based on pilot evaluation findings. P4C is available to develop instruments, gather and synthesize data through polling, trainer feedback forms, observation.

Curriculum Development Principles

A curriculum and associated materials are training documents designed for those who will be delivering the training. They ensure consistent training even as different individuals deliver the material. Remember: How you write is as important as what you say. When developing curriculum, write clearly and concisely. It is important to use plain language that is:

- trauma-informed

- emotionally accessible

- inclusive and non-objectifying

Specifically, the curriculum:

- Provides instructions for delivery methods as well as complete content to deliver

- Provides details on handouts, materials, resources, and logistics

- Has a specified appearance and format, based upon the use of a template and style guide

- Recognize the impact of trauma on children/youth.

- Recognize the impact of trauma on parents and family.

- Support caregivers and caseworkers with understanding and skills related to how to respond in trauma-informed ways.

- Support all parties in identifying and avoiding actions that are often retraumatizing, and in identifying and using practices that support resilience/recovery.

- Recognize the impact of trauma (primary and secondary) on the workforce and caregiving community.

- Be careful about including descriptions of abuse and violence.

- Avoid unnecessarily violent language.

- Avoid objectifying language.

- Avoid judgmental language.

- Be thoughtful about command statements.

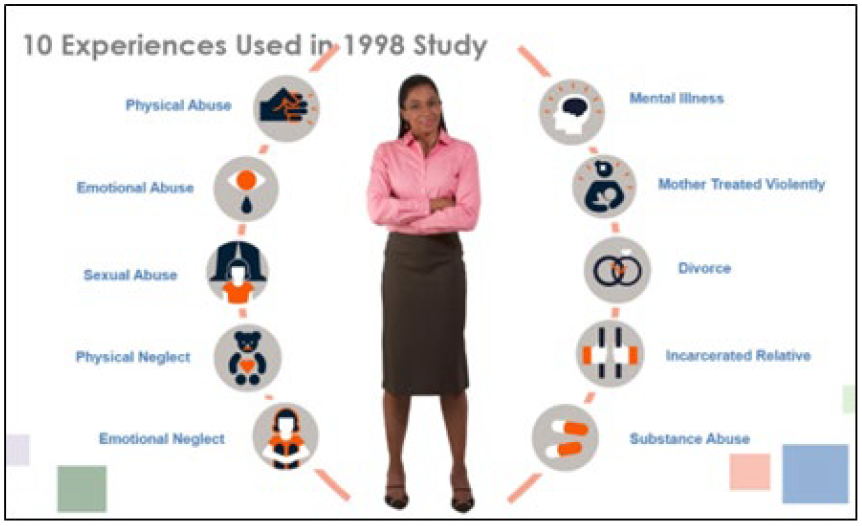

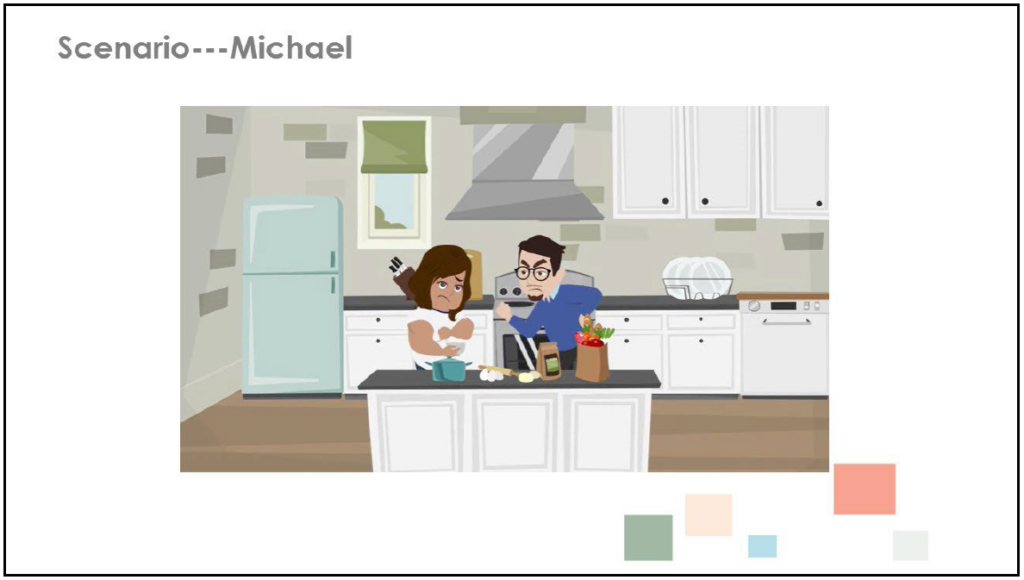

- Use pictures that are metaphors rather than depicting actual abuse, violence, and trauma.

- Be thoughtful about the use of emotion. A little is motivating. A lot is dysregulating.

- Assume several people in your audience will have bigger reactions than you will.

- Ensure that those with broad experience and different lived experiences participate in development (and review) of the curriculum.

- Consider for whom the curriculum will not work: When might there be a challenge? When will cultural norms get in the way?

- Help build cultural awareness and empathy, including around the culture of foster care and culture of trauma.

- Facilitate empathy-building and meet the needs of the child or family with the many cultural backgrounds of the child or family in mind.

- Acknowledge relevant historical and ongoing oppression.

- Use prompts, activities and content related to culturally relevant practice(s) throughout the curriculum.

- Build the foundation: Include an overview of the relevant pieces of historical and ongoing oppression of BIPOC individuals and how this has led to current and historical inequities in the child welfare system. Make sure that both workforce and caregiver learners are exposed to the racism, sexism, and heterosexism engrained in the history of the child welfare system.

- Have those tough conversations: Make sure to build time into your curriculum for intense conversations. Remember that learners all come with their own lenses and experiences. Try to anticipate challenging comments and questions that may be raised by learners and make sure the conversation or activity has enough structure to be productive.

- Focus on culturally responsive skills: Prepare learners to broadly engage with children and families in culturally responsive ways. Learners should be proactive about identifying and responding to a family’s cultural needs, and willing to responsibly own up to mistakes they make to mend relationships and move forward. Caregivers should be aware of the cultural backgrounds of children in their care and strategies for helping them to stay connected.

- Support building equity and inclusivity in homes and workplaces: Offer strategies for caregivers to signal inclusivity in their homes. Empower workers to identify and advocate for best practices in their offices. Encourage supervisors to openly acknowledge racism and oppression as ongoing and relevant in their work environments.

- Model best practices for anti-oppression in curriculum: Partner with people with lived experience and experts in developing your curricula. Use images and scenarios that mirror the diversity of the human experience. Vary activities to support and engage learners of different skills and abilities, including those with limited English proficiency, those who may struggle to hear audio content in videos, and those who may have device constraints when participating in trainings (joining only from phone/smartphone, etc.).

- In addition, the curriculum itself includes a land acknowledgment, clear articulation of antiracist and anti-oppression focus, a learning objective that explicitly addresses antiracist and anti-oppressive content (such as disproportionality)

- Align learning objectives with content and materials.

- Use training partners to collaborate on the design, development, and delivery of curriculum.

- Promote skill development.

- Give examples and facilitate application of the underlying content beyond providing examples.

- Integrate values and empathy and makes these explicit by incorporating value-based learning.

The Alliance incorporates two different experts in the development of curricula:

- The Department of Children, Youth and Families (DCYF) lead – This is the expert in implementation of the policy. This person determines what the curriculum content looks like in practice. This person helps in development of practice scenarios and what is happening in practice. The lead helps identify initial questions that need to be addressed in the training, trends in practice, and program specific details, including:

- Helping scope the training

- Explaining the reason behind the request for the training

- Identifying learning objectives

- Reviewing and offering feedback on the training

- Collaborating with the Alliance lead to finalize the training

- SME – This person offers professional content expertise and/or lived expertise. SME may include Child Welfare Training and Advancement Program (CWTAP) representatives and Tribal partners. The person will have one form of expertise, which may include: being recognized within their community as having expertise in the issues addressed by the curriculum; deep expertise in the research literature; understanding of accepted best practices and/or evidence-based practices; knowledge gained through direct, lived experience with the content of the training (such as foster care alumni, long-term caregivers, parents). The SME:

- Offers expertise and knowledge on specific components of the training

- Reviews and provides feedback on components

The Tribes, as well as the Office of Tribal Relations, and other Indigenous-led organizations may serve as SME and/or as leads, depending on the training experience being designed.

- Events flow from a needs assessment that informs the content.

- Events use strategies and methods that are engaging and inclusive.

- Events are anchored in adult learning and is research-based and theory-driven.

- Events provide adequate time for instruction, learning and post-event support.

- Events prioritize the learner and their needs.

- Events are scaffolded appropriately and meet learners at different points in their role.

- Events break down complicated content into manageable pieces.

- Events integrate both knowledge, skills and values

- Interventions and approaches taught in learning events have evidence to support their use, including research scholarship or best thinking in the field.

- They promote best and cutting-edge practice.

- They are theoretically sound.

- They are guided by a theory of change or logic model.

- They are explicit about what learners will learn.

- They describe outcomes that are measurable.

- Outcomes and goals are stated clearly and written from the learner’s perspective.

- They are succinct and state one to three objectives with approximately one learning objective per hour.

- They are anchored and directly tied to training content, practice, and what the learner is expected to achieve at the end of the training.

- They are suited to the level of the course.

- They are achievable and realistic.

- They create a process where learners are able to demonstrate achievement of learning objectives.

- They model equity and best practices.

- They build skills around workplace equity.

- They support learners in developing skills to do culturally relevant work.

- They provide information about current inequity related to our system.

- They explicitly address antiracist and anti-oppressive content (such as disproportionality)

- They are subject to robust evaluation that continuously informs their development.

- Their content and materials are regularly reviewed and updated.

- There is an ongoing review process involving experts and the community.

Phases of the Curriculum Development Process

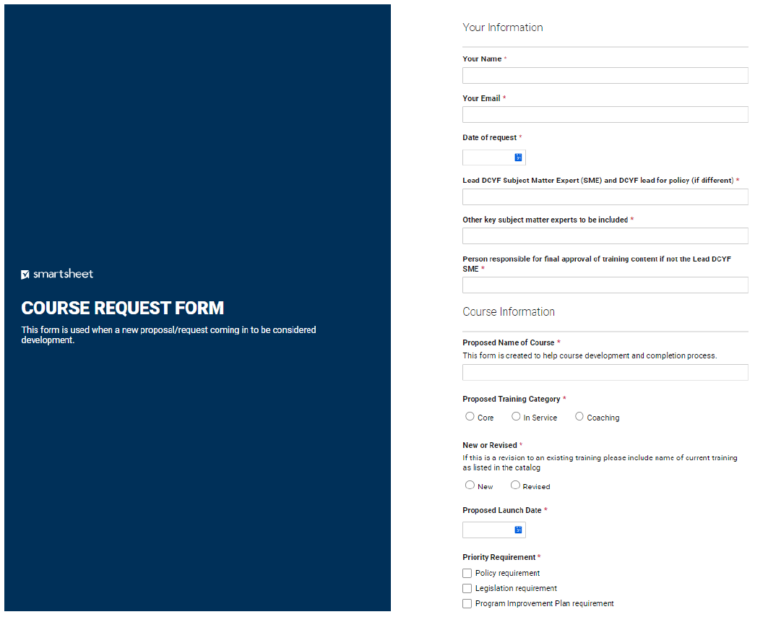

PHASE ONE: Accepting a Course Request

How does the Alliance determine what trainings will be developed and why? Here is a review of the process, to provide context for how a particular training request may have come to be.

- Process begins with:

- DCYF liaison will provide a link to the course request form, no matter what division. DCYF liaison works internally to determine the need for Alliance involvement.

- Alliance liaison will provide a link to the course request form as needed to initiate course development.

- Course requests can be submitted to DCYF and the Alliance throughout the year.

- Assigned DCYF liaison and/or requester, in consultation with the Alliance liaison, completes a course request form for a new or revised training curriculum.

- Course requests are submitted via Smartsheet. The request includes information about initial ideas related to the need for the course(s), resources for the training, timeline, and other important initial thoughts.

- See Appendix B: Course Request Form.

- Request is reviewed by Alliance Liaison, Alliance Leadership, and DCYF liaison for consideration to approve or decline request.

- The highest priority is given to the Annual Plan and Deliverables.

- Other considerations to approve or add courses to the annual plan include:

- If the course is not included in the Annual Plan, a collaborative decision is made based on capacity, resourcing, scope, and relevance to the Alliance’s Strategic Plan.

- At times, a request may be received from Alliance staff or other partners in the training system, to be reviewed by the Alliance liaison.

- Other considerations to approve or add courses to the annual plan include:

- The highest priority is given to the Annual Plan and Deliverables.

- Folder for curriculum work plan is created by Alliance liaison and assigned in the Smartsheet tracker (template).

- Assigned curriculum development (CD) lead and workgroup assignments include developing Terms of Reference, if appropriate, based on the scope of the project to determine roles and responsibilities.

- Assigned CD lead manages and owns the project plan within Smartsheet (adding in tasks and assignments).

- The people assigned are responsible for updating their tasks and timelines.

PHASE TWO: Developing a Training Team and the Kickoff Meeting

The curriculum developer reviews the training request and starts considering who might participate on the training team.

The training team is a group of people who will support CD and implementation for a particular course. The core team members will design, review, or inform every aspect of the training development and initial implementation.

For more information about the roles and responsibilities see the Training Activities Charter.

See Appendix C: Training Team Roles for a description of the various roles that might be relevant to a given training.

Others involved in the training and with the training team may participate in less regular or structured ways but still provide valuable insights and support excellence in curriculum design. The Alliance is committed to integrating multiple cultural perspectives, and authentic/lived experiences, into the development of training. Curriculum developers and training teams need to think broadly about who is engaged to ensure this principle is reflected in work on each curriculum.

- The curriculum developer reaches out to schedule a kickoff meeting (on very small, well-defined projects, email communication might substitute for this meeting). The meeting should include individuals already identified on the training request, the Alliance curriculum developer, and perhaps a lead facilitator if identified. An instructional designer or SME may also be invited if they have been identified early on as being involved in the project. The Alliance evaluation partner, P4C, should also be invited.

The following topics should be addressed:

- Understanding the need or problem behind the training request.

- One of the first tasks of the training team is to discuss the training request and better understand what needs or challenges are happening in practice (of staff, caregivers, or another target audience) that necessitate the request. What data can DCYF provide that help the team understand current practices and behaviors of the target audience and challenges in shifting those behaviors?

- When the team can clearly understand what is happening and what the needs, gaps, and challenges exist, they are better able to design a training that targets these needs. Assumptions not based in evidence or broad, purposeful collection of data and information can lead to trainings that don’t address the actual causes of, and contributors to, the problem.

- Consider the following:

- What outcomes are we trying to impact?

- What needs to be different and why?

- What is keeping behavior from changing? What barriers should we acknowledge and plan for?

- What resources do we have to help support and sustain change?

- How will the training help the participant (not just the family/child/child welfare system)?

- Where are the learners at right now related to values, knowledge, and skills relevant to the challenge or change?

- What efforts are already underway?

- How will we know if the training is achieving the goal?

- A related consideration is what practice or behavior should look like relative to the task or focus of the training. What are the steps, cognitive processes, skills, or components that are needed to complete the task well? (For instance, if the challenge or problem is that caregivers are sometimes punitive or harsh in their discipline, what discipline practices do we want to see? How would those look across different challenges, developmental stages,

and relationships with children? If caseworkers are failing to create meaningful connection and engagement with parents, what are the steps, techniques, and behaviors that they should use to create this connection?) - Discussion focused on understanding what practice should look like may involve identifying sources of information (relevant research, etc.) on best practices. We may need to identify experts or written sources. Curriculum developers should not be expected to independently identify steps, processes, or examples of “best practice” in a vacuum. Sources of information on these practices should be sought and approved by the training team.

- See Appendix D: Sources of Reliable Information

- Identifying the goal(s) of the training

- Once the problems or needs and alternative practices and supports are better understood, the team should determine the overall goal or goals for this training.

- A goal is not a topic. The goal of the training is not child development, or “the new home visit policy.” Those are topics that might be covered during the training. A goal describes what the training is meant to help people do.

- “It is required” is also not a goal. If the training is required or has been mandated – why? What specific skill or practice is not happening, that this training is meant to support?

- While larger trainings may have more than one goal, a shorter training would typically have only one. Goals should be as clear and specific as possible. A goal of “improve practice” is unlikely to help drive training development. A goal of “build skills to support genuine engagement and collaboration with youth 15 –21 years old” is much more helpful in terms of how it might guide what should and shouldn’t be included in this training

- Expertise and experience are still needed

- Who else should be added to the training team (bringing expertise relevant to the goal or to implementation or development)? What are next steps to bring them in?

- Modality

- What modality is the best fit with the overall goal(s) of the training? What implementation or other considerations or constraints might be relevant to choosing a modality (or multiple modalities)?

- See Appendix E: Training Modalities and Guidance

- Training time (initial estimate)

- What is the initial thinking about the training time required to achieve the goal? The length of the training ultimately depends on the specific learning objectives and the training modalities and activities selected, but an overall idea is possible and helpful at this point.

- Evaluation and assessment

- What approach to evaluation will be most helpful in the design, revision, and assessment of the training? The P4C training team member can speak to options, and the DCYF lead can address any existing directives or outcomes that must be measured.

- The answers to these questions will remain conditional; you may have to change your mind as you do the work of creating objectives and an outline. But having even conditional answers is important in guiding the next steps.

- Project plan/timeline

- Lastly, the team must understand the overall steps associated with designing curriculum, the points at which feedback will be requested, methods to provide feedback, and timelines to do so. An overall project timeline should be created at the kickoff meeting, though often it’s regarded as very provisional, since large gaps in what’s known may still exist at this point

Depending on the size and scope of the project, it may take more than one meeting, and associated emails and follow-up, to answer the questions above. Development should not begin until the questions above have been considered and there is reasonable consensus on answers.

This phase is informed by each of the CD principles. Integrating the consideration of these principles from the start will improve the quality and impact of the training.

In the kickoff meeting it may be helpful to share the curriculum principles and discuss each, as they apply to the agenda item. For instance:

- When identifying members of the training team and others who will inform training development, consider the principle that Alliance curricula use experts (#5), represent multiple cultural perspectives (#2), and are evidence-informed (#7)

- When discussing the need for the training and what behavior should look like, consider how the recommended practices and behaviors can be trauma-informed (#1), consider how training participants from a variety of cultural backgrounds might approach or understand the task or skill, and how families with different cultural identities might want to engage with and/or be engaged by our training participants (#2). Consider whether the recommended practices advance our values related to antiracist, anti-oppressive practices (#3) and how the training will specifically make these connections for our participants. How is the behavior we want to see like other approaches or behaviors that participants already know about, how does this approach line up with the practices folks in other roles use or should be using, and how can critical thinking help participants identify when and how these changes or skills should be used (#4).

- When considering modality, we’re applying adult learning theory (#6).

- When identifying a goal, we’re responding to principle #8 (have clear outcomes, goals).

- When discussing initial ideas about evaluation and assessment, we’re responding to principle #9 (ongoing quality assurance)

PHASE THREE: Develop Initial Learning Objectives

The next task for the training team is to create a list of learning objectives that support the goal of the training.

Learning objectives are how you will operationalize your training goal. They describe what participants will learn in the training and should map easily to the activities and content that will be developed in the training.

At the Alliance, our learning objectives should meet three general criteria. They should be:

- Learner Focused: They describe the experience of the learner, not the activities of the trainer/facilitator.

- Verifiable/Measurable and Realistic: We could create reasonable ways to assess whether the learner achieved them.

- Active and Skills Focused: They describe a process of active learning, where participants in the training are engaged beyond listening, and are participating in a variety of activities that support them in achieving the objectives

See Appendix F: Learning Objective Development for ideas about how to write measurable and active learning objectives.

There is often pressure to address a large range of knowledge, skills, and values in a training. It’s important to think realistically about the learner experience, and what is achievable in the training delivery. Learning objectives will also inform the evaluation, so that we measure if the objectives were met.

Learning Objectives fall into three categories: Knowledge, Skills, and Values.

Knowledge learning objectives describe what participants will come to know, or better understand, or in some cases be able to apply and operationalize, because of the training experience.

Our participants (across roles) are consistent in their desire for learning to be directly grounded in their work or role. While it might be interesting to learn about how trauma affects the brain or the latest research on the impacts of parental mental health struggles, our training participants also want to know what they can do with that information. What should they change because of

this information and how? They want information and theory translated into practice for them.

It’s very common that we have an initial impulse to include many knowledge objectives. Be cautious and remember that knowing does not equal doing. We often think that if participants knew that it wasn’t effective to yell or spank, if they knew that family time was important but could also be traumatic, if they knew that creating a strong connection with a parent would result in a better safety assessment, then they would behave accordingly. The problem is that knowing these things isn’t the same as bringing them to life. People need skills related to each of these situations. We could ensure that knowledge objectives related to these topics were met, but this would not impact what happens in the field, because knowing is necessary but not sufficient to solve these problems.

If most participants don’t know something, and that is getting in the way of them doing a skill or doing it well, then a knowledge objective is needed. If they generally do know something but the behavior still isn’t happening, this is an issue related to skills, motivation, or (individual or systemic) barriers. No amount of additional knowledge will solve it.

Skills learning objectives describe what participants will be able to do (or do better or do more efficiently, etc.) because of the training experience. Because the Alliance delivers primarily skills-based training, the training team should think critically about any training that has no skills objectives. There are efficient ways of distributing information that fall outside the scope of a training.

Skills learning objectives often take the most time to achieve. It’s common that participants may watch a video, practice all or part of the skill, role play or critique existing work. Feedback on performance is also critical to developing a new skill. These all take time. Applied activities often take 30 minutes or more, depending on the depth of practice. These are important considerations when determining which skills objectives are needed, and whether the time that we identified for the training is or is not realistic.

Values learning objectives speak to the underlying belief or core value that explains why the participant might want to use the skill.

Targeting beliefs or attitudes can create behavior change even in the absence of specific skills training (but more powerfully in combination with it). Values objectives increase or sustain a participant’s motivation to use the skill, even when it might be easier in the short term to approach a situation in another way.

As the training team thinks about what practice looks like now and what shifts may be needed, one important consideration is whether most participant’s existing values, attitudes or beliefs are getting in the way of them consistently using the behaviors we want to see. If so, then values objectives are an extremely important component of achieving the goal of the training. If not, they may not be particularly critical.

While each individual participant doesn’t need to hold the same set of values, they deserve to have training experiences that make the values of DCYF and the Alliance explicit. The Alliance assumes everyone is doing the best they can (parents, children, youth, social workers, supervisors, managers, and leaders). The training environment is intended to promote critical thinking and new ways of knowing and understanding to reduce bias and increase equity.

Values objectives should align with the topic being presented. Be mindful of the following principles developed by Jill Berrick from her book The Impossible Imperative:

- Parents who care for their children safely should be free from government intrusion in

their family. - Children should be safe.

- Children should be raised with their family or origin.

- When children cannot live with family, they should live with extended relatives.

- Children should be raised in families.

- Children should have a sense of permanence.

- Families’ cultural heritage should be respected.

- Parents and children (of a certain age and maturity) should have a say in the decisions that affect their lives.

The foundational message of Dr. Berrick’s book is that people involved in the child welfare system in many capacities often find that a particular decision or action will prioritize one value while conflicting with another. Sometimes there is no obvious path forward that aligns with all the values participants hold (personally or professionally). Where this is a relevant concept to highlight within training, it may normalize the challenge that staff and caregivers face in their roles.

Typically, the Alliance leads and curriculum developers will guide the discussions outlined in chapter 2, The Training Team and Kickoff Meeting. Then they will leave the kickoff meeting and develop a set of learning objectives that will support the goal(s) of the training and are appropriate to the time and modality initially described.

It can be helpful to have a follow-up meeting to discuss these objectives, allow for feedback, and address any big mismatch (e.g., We said this was a 2-hour training, but we have 12 learning objectives that we all agree are needed and this probably puts the training at around eight hours). This can also occur over email.

As learning objectives are being developed or reviewed, consult the Alliance curriculum principles, and ensure we’ve addressed important considerations (such as being trauma-informed, incorporating various cultural perspectives, antiracist, include expertise, etc.). This may guide you in editing, revising, or adding objectives.

Generating an Outline

Once the training team agrees about the learning objectives, a high-level outline should be developed. It should identify the order in which the learning objectives will be trained, some initial ideas about how they might be supported, and best guesses about time.

PHASE FOUR: Designing Active Training

At this point, the training team has articulated the goal of the training, and the learning objectives describe how the training will support learners toward that goal. The curriculum developer may have created a loose outline that groups the learning objectives into conceptual blocks in a particular sequence.

Alliance trainings should be active and engaging, because this is the best fit with how adults learn. Adults arrive with life experiences and existing knowledge and skills. They also have competing demands for their time. For their brains to be engaged, we need to have (and keep) their attention. This means that trainings should be offering them something to do every few minutes. This could be small (“Give me a thumbs up if this fits with your experience as a caregiver” and “Find a partner and jot down as many examples as you can of…”) or large (“Read the scenario and as a group come up with at least three approaches you might use with this caregiver to help you understand whether the placement can and should be maintained” and “Role play this situation using the skills we just reviewed”). Gamification is the application of game design elements to educational settings with the goal of increased engagement in learning. Trainings must regularly ask participants to engage with the material and each other, and gamification is a wonderful strategy to consider.

One challenge we’ll need to overcome is that our learners have a range of experiences, knowledge, values, and skills. Selecting activities that are “just right” to support your objectives will be especially difficult given this diversity. It’s very tempting to train to the least knowledgeable and least skilled folks in your audience. This leads to a training that’s boring for most participants.

What is the alternative? Creating activities where participants work together to utilize their collective knowledge and skills. Simulation is a technique to consider that amplifies real experiences with guided experiences that evoke or replicate substantial aspects of the real world

in a fully interactive manner. Debriefing is the most important feature of simulation based learning (further defined in Appendix G: Active Learning Definitions and Guidance). Less informed participants will learn from more knowledgeable ones. More advanced participants will

offer comments and model skills that will be helpful for everyone. Facilitators then are responsible only for providing the information, application, or demonstration that none of the groups generated on their own. This is an approach that can be used when developing activities related to knowledge, values, or skills objectives.

Here are ideas about specific activities and types of engagement that might work best for each objective type. Many more options are possible and listed in Appendix G: Active Learning Definitions and Guidance.

Matching: Provide definitions and/or examples of key concepts or vocabulary (or even skills) and have participants match them. Depending on the group, you often do not have to discuss the definitions first. Participants working in groups can find their way to most answers. You can encourage guessing. Then during the debrief groups who got the correct answers can explain why, and facilitators only need to refine the points that were missed.

Have them tell you: Do you need to ensure that everyone knows a timeframe or fine points of a policy? Just have the group call them out. Note them on a whiteboard (virtual or physical). Then move to some type of application or challenge so they can do something with this information. If many people in the group know this information, there’s no reason for a facilitator to be the one

to review it.

Examples (yes/no) and explanations: Give people an example of the concept in practice and ask them if it’s been applied correctly. For instance, “Ms. Thomas agrees to allow Suzanne to live in the home for the next 4 days and to make final decisions on discipline and feeding.” “Is this an acceptable safety plan item, based on the criteria we just discussed? Why or Why not?”

Read and reflect activities: Have participants read information that you might have been tempted to lecture on. This can be a published article or a handout you developed. Then have them do something with it, either in a group or individually. Apply it to a real experience they’ve had. Generate a list of criticisms and strengths of the approach. Write down three contexts in which they would use this information to guide them in approaching a situation differently. They are engaging with the new learning in an active way and the engagement will increase their retention of the information.

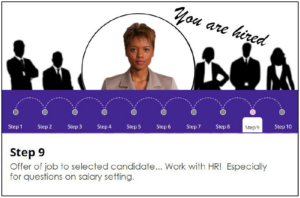

Sort/order activities: Need people to know the steps of a process? Have them put them in order. It’s ok if it’s just a guess (in fact, this may increase participation). Then debrief the correct order and see what participants can explain about what happens in each step. Fill in or correct information as needed.

What doesn’t usually work:

Lecture: It’s generally boring and doesn’t leverage the collective knowledge of the group

No matter what actions or activities you choose here, it’s important to deliver content related to values in a respectful way. Sending the subtle message “If you cared more about this then…” is a sure way to offend many participants and will not be effective in changing hearts or minds.

Testimonials: Stories are an incredibly effective way to impact people’s opinions or ideas on a topic. When people share their lived experiences, it can have a huge impact on how participants feel about folks in the role of the storyteller. Most people don’t get to hear firsthand accounts of what addiction is like, what it feels like to have the government tell you your child is not safe with you, what it feels like to open your home to a child you’ve never met (or to watch them return to a parent you hope will be kind and safe). Videos and panels are ways to create affective shifts and achieve values objectives.

Simulation games and roleplaying activities: (different from a simulation or roleplay) When participants are assigned a role or set of life circumstances and need to navigate a particular daily life activity with the challenges and circumstances their character faces, we can often simulate the challenge of being in that circumstance. This can build empathy for folks we work with who live within those same constraints. This includes activities like “In Her Shoes,” or games where the outcome at every point is determined by the life experiences that were assigned to you at the beginning. These activities are much more structured than simulations or role plays where participants can say whatever they like as a character. The simulation game or activity typically forces choices between pre-determined options, and the participant isn’t trying to demonstrate or practice a skill, rather the focus is on experiencing a particular circumstance that might be common for folks they often work with (e.g., applying for financial benefits, taking public transportation to get to an appointment with three children under 5, being a young adult in foster care, etc.).

Using credibility (e.g. who will they listen to?): When we can use video clips (or quotes) from folks who have a lot of credibility with our participants, their endorsement of a set of views, beliefs or practices can go a long way. Participants may or may not listen to us but may place a lot of value on a particular leader or celebrity or group. Does NICWA endorse this practice? Did Brene Brown do a talk about it? Is there a video of the leading scientist discussing the impact? These may ‘hit home’ much more than a trainer saying the same thing.

Talking “as-if”: We may know that practice in the field (or caregiving in most homes) often doesn’t look like we want it to. We can still take care to describe the practice in great detail, as if it were often or usually true. This gives participants a repeated roadmap and expectation that there are people making this work. It gives folks who are interested in making a change some hope that it’s possible (along with offering knowledge and skills to get them there).

What doesn’t generally work:

You’re wrong: Activities that make people feel “wrong” or that make people defend their behavior are ineffective (at best). Look closely at the activities and discussions around your values objectives. If there are places where participants are likely to be pulled into arguing for the status quo, consider revising these. Always acknowledge the barriers that may be getting in the way of folks doing better work (these can’t become excuses, but we have to acknowledge reality). Then think about what we can do.

Moralizing: Participants want to see themselves as good people, who do good. And it’s unlikely that any of them came to their role or this training with evil intentions. Training can never leave folks with the impression that we think “if you were really a good person then you would…” While it’s fair to recognize the negative impact that some behaviors or practices might have, we should not imply that anyone showed up with bad intentions, or that their behavior is evidence of their moral insufficiency.

Data and statistics: These are helpful once folks have come to value something, but when data don’t support someone’s existing beliefs, they are typically not accepted by that person (at least not initially). There is a lot of research on this topic. Data are great at making a case to neutral folks, and helpful at honing motivation in folks who already believe or feel a particular way. But they’re not that helpful in changing minds, so not particularly effective to support your values objectives. Save the data review for after the story/endorsement/other activities that help folks make that values shift.

Practice plus reflection plus feedback (simulation and roleplay): People learn skills by trying them out. Simulation and roleplay are the two main ways that skills can be practiced in their entirety. Activities that ask them to reflect on specific aspects of how they performed or would perform a skill can increase skill development. Feedback from an experienced facilitator, delivered in ways that feel safe and supportive, will further the impact of practice and reflection.

Scaffolding: Most skills that we would like our participants to learn are made up of many smaller skills and take a lot of time and repetition to do well. Practice without taking the time to build up these smaller skills, and to understand when and why they’re used, is often not effective. We must often design a series of activities that lead up to a simulation or roleplay.

Direct instruction: It’s not enough to describe what a skill should look like; we must provide direct instruction about the skill whenever we believe that a good chunk of our participants don’t already have the skill mastered. For instance, telling folks to engage with parents respectfully, or to involve children in decision-making is not helpful if we don’t discuss the main components of these skills, provide examples, dissect real-world challenges, and have people try out the approaches we have taught. We must break down the skill and give some direction as to what the real-world behavior actually looks and sounds like.

Demonstration: People benefit from seeing the skill used in a realistic way. How does the person in the video respond when the child doesn’t comply the first time? How does the caseworker use silence or normalizing when the parent denies having any ideas about how to address the problem? Participants deserve to see the skill and to see it in a context that’s not the best-case scenario. It can be helpful to pair a demonstration video with a critique, so that participants who are still weighing their motivation to use the skill can put their concerns out into the open and have others respond to them.

What doesn’t generally work: Throwing people into practice without providing activities to model the skill and develop some critical thinking about when and how to use it. If participants can practice the skill with no instruction, they are simply repeating what they already know, and not developing any new skills. If they can’t, more practice without instruction won’t help. Scaffolding must be built in, as well as some mechanism for folks to reflect and/or receive feedback that loops back to the instruction related to what the skill should look like and why.

The next step, following identification of the learning objectives, possibly a high-level outline, and some reflection about what types of activities might support the objectives and goal, is to create an in-depth outline (see Appendix H: Example Outline).

This outline will describe the training from opening to closing. The outline should show each section of the training, the learning objective(s) supported, ideas about what type of activities will be used, and an estimate of how long the segment will take. It will also budget time for breaks (typically two 10-minute breaks per three hours of webinar; in-person training sometimes uses one 15-minute break for every three hours). Generating this in-depth outline requires thinking about each objective and how best to support it.

It’s important that the training is engaging and flows coherently from start to finish. Review your outline – thinking about the activities you selected – and consider whether you’ve met the following criteria:

- All (or nearly all) of the activities and content advance the learning objectives.

- Engagement is frequent and periodic, not just at the end of a long block of information.

- Engagement happens in a variety of ways and with a variety of modalities and using different sized groups for collaboration. Video, audio, instructor-led or participant-led, direct application, brainstorming, compare/contrast, roleplay, simulation, large group, small group, pairs, individual reflection, tactile or sensory, read/write, visual/special, etc.

- Each activity has enough time allotted to provide instructions, answer clarifying questions, do the activity, and discuss/debrief/recap.

Sending the Outline for Feedback

The curriculum designer should send the in-depth outline to the training team for feedback. The curriculum designer might consider sending along a structured tool to receive feedback, so that the team knows what specific considerations it should weigh in on. Another helpful tool to send along with the in-depth outline is the curriculum guidelines. Both the training team and the curriculum developer should review the outline with these in mind.

Creating the Major Activities

At this point, you have all the building blocks that will go into your draft curriculum and have received feedback on your in-depth outline. Rather than starting at the beginning and writing the entire training, we recommend developing the largest activities on your outline first, along with the handouts, videos, or other materials you anticipate needing to create. This allows you to send these pieces to the training team for feedback early, since they are the parts of your curriculum most likely to need significant revision. Case scenarios, the questions we ask about them and the talking points/debrief following an activity often take multiple rounds of revision, and it’s good to start that process early.

As you develop your main activities, make sure you provide written instructions to participants and facilitators for all activities that require more than a sentence or so of explanation. Review instructions to make sure they are clear and concise, and that they can be provided in writing to virtual participants.

Also consider whether they will be at the right level of difficulty for most participants. If resources, information, or prior practice (scaffolding) are needed, ensure this is accounted for in your training outline.

Remember to incorporate and consider the curriculum guidelines. Application specific to activities and to overall curriculum is addressed briefly in the sections below.

Trauma-Informed, Antiracist, Anti-Oppressive Curricula

All activities and interactions within a curriculum should be trauma informed. This is especially important when the topic of the training is not trauma, because it models that considering trauma is the default approach, we all take to this work. For some considerations on what this means, see:

Appendix M: Trauma-Informed Principles (CDC and SAMHSA)

Appendix N: Trauma-Informed Trainings

All activities and interactions within a curriculum should be antiracist and anti-oppressive. This is especially important when the topic of the training is not about race or oppression, because it models that considering racism, oppression, and cultural strengths and preferences is the default approach we all take to this work. For some considerations on what this means, see:

Appendix O: Creating Antiracist and Anti-Oppressive Curricula

Appendix P: Indigenization of Learning and Skill Development

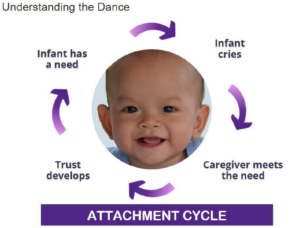

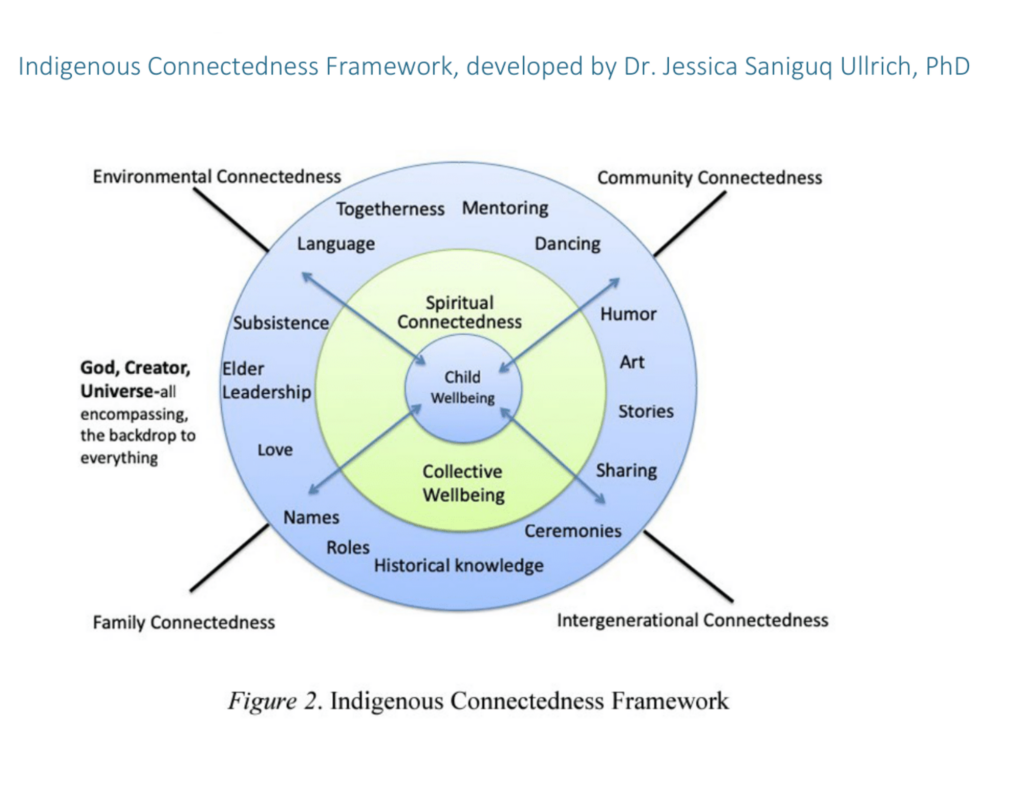

An example of a framework for understanding families and children involved with child welfare (across our participant’s roles) that is trauma-informed and centers Indigenous knowledge and ways of being is the Indigenous Connectedness Framework, developed by Dr. Jessica Saniguq Ullrich, PhD. Integrating this framework, or other culturally relevant ways of understanding children, their families, and their paths toward healing, into activities or discussions can support our goals in both regards.

Appendix Q: Indigenous Connectedness Framework

Send along the major activities, along with instructions, debrief questions/answers/talking points, and any accompanying handouts to the training team for feedback. Consider providing them with a tool to structure their feedback, including the curriculum guidelines.

Modifications for eLearning

When the training will be an eLearning, the curriculum designer may still need to develop handouts, scenarios, or specific content related to activities. These should be developed and reviewed as above. It is important to work in collaboration with the instructional designer, who can advise of any technical issues that will impact the activity and help the curriculum designers select the best type of activity to support the objective within this modality.

Creating the full Draft Curriculum

By this point, you have developed a detailed outline which identifies activities that support your learning objectives. You have developed drafts of your main activities, handouts, and other parts of the curriculum that will support instruction and received feedback from the training team.

You have considered how to best support learning, ease of facilitation, and how to embody the curriculum principles.

You are now ready to develop the full draft curriculum and participant guide.

Use the curriculum template as you create your full draft curriculum, to document your talking points, critical questions, activity instructions, etc. The template supports ease of facilitation, makes it easy to find particular types of information about a course, and supports the ability of federal reviewers to make reimbursement determinations (so that we get the maximum allowable funding for each course).

See Appendix I: Alliance Facilitator Guide Template (LINK)

In most cases, trainings include PowerPoint slides, which serve as visual guides to the facilitator and participants throughout the training. Information on visual design and branding is included in chapter 5.

At a minimum, the opening of a training event should include:

- A territorial acknowledgment (see Appendix Q: Territorial Acknowledgments)

- Introduction of the Facilitator that includes preferred pronouns

- Brief overview of the structure of the training (length/stop times, breaks, materials)

- Brief overview of the goals or learning objectives

- For in-person trainings, any information about restrooms, eating areas, etc. that participants need to be comfortable throughout the training

Most trainings will also benefit from:

- Participant introductions (invite people to provide pronouns, if comfortable and provide an opportunity to share something about self/content/etc.)

- An initial activity (short or more involved) that facilitates human connection and begins to build trust between participants

- Expectations for the training (provided by facilitator or generated by the group)

Watch out for boring openings. Participants should be doing something within 5 minutes of the training start time. A short ‘hook’ is often used – this is a quick interaction that introduces participants to the main problems the training will help with. It’s often something they may be able to respond better to, work out or solve at the end of the training.

At a minimum the closing should include:

- A review (preferably active) of what should have been achieved by the training

- Thank participants for their time/effort/attention

- Information about how to complete the evaluation

Most trainings will also benefit from:

- Activities that allow participants to apply what they’ve learned

- Time for planning or reflection (paired, individual, etc.)

- Information about how to continue to learn or get support (coaching sessions, staffing, other trainings)

If you are struggling with any aspect of design during this period (from in-depth outline to first full draft curriculum), one source of support is the Instructional Design team. They hold expertise in visual design, but also in designing activities for adult learners in general and can be helpful at any point as you build your training.

A written draft for every eLearning should be created to allow all team members to provide feedback. All the audio and text that will be used in the eLearning should be included here is draft form. Larger activities (that you may have already created) are built into the draft curriculum (or referenced and attached). For example (insert the “Which Child Needs an Evaluation?” activity here). Reviewers and instructional designers should be able to read the draft curriculum and understand what learners will hear and read from start to finish. While this is a draft and open for feedback, the content and structure of the course from start to finish is captured within this document.

If there are visuals (diagrams, pictures, etc.) that the instructional design team may want to incorporate or reference, indicate that, and send and attach the files.

While participants in an asynchronous training (such as an eLearning) will not need a Participant Guide, the curriculum designer may develop a resource document that participants download and reference following the training.

Once the full draft curriculum is written, curriculum designers circulate it to the training team and use the agreed upon timeframe for each team member to provide any feedback. Tools are available to help reviewers give focused, organized feedback. Curriculum designers (in collaboration with instructional designers on some projects) review all feedback and make determinations about what changes and edits will improve the training and the learner’s experience. Review and feedback tools, and the process of determining what edits and changes to make, are discussed in chapter 6.

Aligning with CD Principles

The curriculum principles can be a helpful guide when designing activities, including scenarios. At the point of completing the initial curriculum draft (for live trainings or eLearnings), reviewers should be prompted to provide feedback on whether curriculum principles 1,2,3,4,7 and 8 are evidenced, and how.

Principle 5 (adult learning) is best evaluated by members of the training team with expertise in curriculum design. Principle 6 (use expertise) is built into the process and may or may not be apparent within the curriculum itself. Principle 9 (quality assurance) is designed and implemented in tandem with the training but isn’t generally apparent within the training curriculum.

PHASE FIVE: Learning Experience Design

The design process starts with a needs analysis, audience research, and a carefully crafted plan that includes creative ideas and a compelling message for the target audience. By strategically organizing graphic elements you can capture the audience’s attention long enough to deliver your message to sell a product, advertise a service, or establish a brand.

In eLearning, stakes are higher. eLearning design involves more decisions than creativity and aesthetics alone. The work is not meant to be consumed and forgotten. Accomplishing this requires a thorough understanding of how we process and retain information in today’s world. In addition, training professionals need to master the various digital software and platforms and develop visual design skills, so they create high quality eLearning courses that establish credibility and build trust with the remote learner.

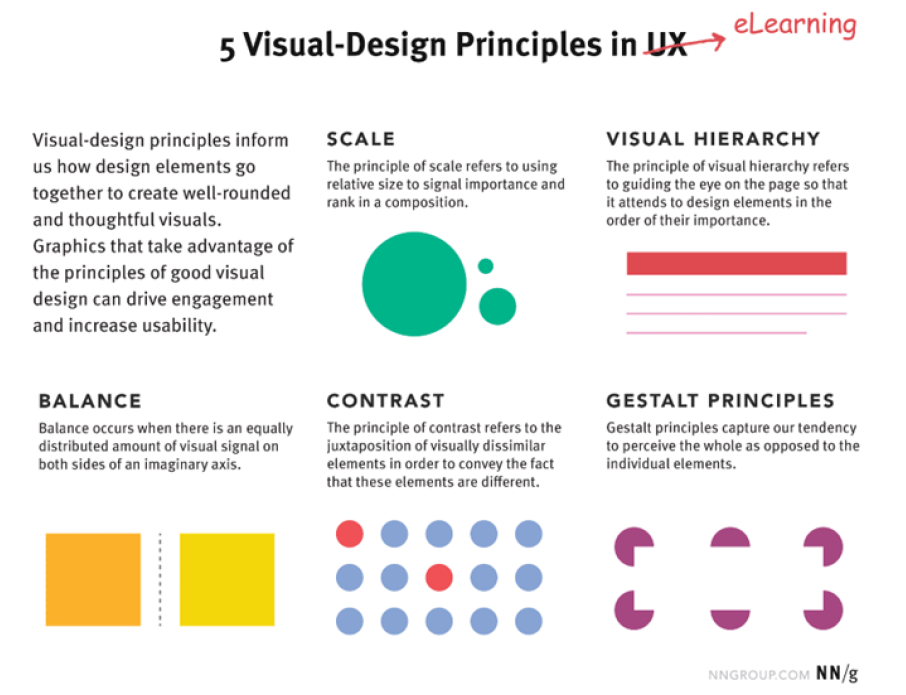

For a seasoned training professional, this transition may seem daunting. Following the basic visual design principles listed in this guide is an excellent first step in the right direction.

The basic visual design formula is universal whether it is for print, web, or eLearning design.

1. Scale

- The principle of scale refers to using size to signal relative importance and rank in composition. When something is bigger, it gets more attention. Therefore, the most important elements are larger in size in a design than the ones that are less important.

- A good design generally is made from a combination of no more than 3 different sizes, as they develop a visual hierarchy and create variety within your layout.

- When the principle of scale is properly applied, the right elements are emphasized and learners’ attention will be easily attracted to them.

2. Visual Hierarchy

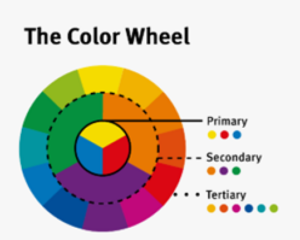

- The principle of visual hierarchy refers to guiding the eye on the slide so that it catches the elements in order of their importance. Visual hierarchy can be done through variation in scale, color, spacing, value, placement and other signals. Like the principle of scale, we can use 2-3 typeface sizes to indicate what elements are most important or we can use bright colors for important items and muted color for less important ones.

3. Balance

- The principle of balance refers to an even distribution of visual weight. The visual elements must be equally distributed, but not necessarily in symmetrical manner.

- Balance can be:

- Symmetrical: design elements are symmetrically distributed relative to the central imaginary axis

- Asymmetrical: design elements are asymmetrically distributed relative to the central axis

- Radial: design elements radiate out from a central, common point in a circular direction.

4. Contrast

- The principle of contrast refers to the juxtaposition of not visually similar elements in order to convey these elements are different. Contrast provides a noticeable difference to the eye to emphasize the design elements are distinct.

- Contrast is often implemented through color.

5. Contrast

- Gestalt Principles

- Gestalt principles refer to humans’ tendency to perceive design elements as a whole as opposed to the individual elements.

1. Copyrights Material

- Do not use any assets you find online until you understand their copyright requirements. Giving credit is not enough.

- FAQ on copyrights

- Fair use of copyrights

2. Templates

- Do not assume that the templates you will find online are well designed, user-friendly, or accessible. The best practice is to use the templates provided by the Alliance. If no template exists for the work you are taking on, take care to ensure you are attentive to considerations like accessibility in using a found template.

3. Metadata

- Do not remove the existing metadata but add your organization’s name, keywords, and information about your project. With detailed metadata information, you can find assets quickly in your digital asset management system.

- What is metadata?

1. Basic Principles

- When it comes to visual learning design less is best, and consistency is critical. Easy-to-scan layouts and meaningful visuals will serve as a scaffolding for the learners.

2. Cognitive Load Theory

- As a training professional you already know that our working memory has limited capacity and can be overwhelmed quickly. Avoiding visual clutter and following a predictable design pattern reduces the cognitive load, which allows learners to retain information longer. • Organizing the Page: Layout of Page Elements

3. Location indicator

- Learners want to know where they are in the process and where they are going. Scaffolding is important for adults; therefore, the consistent use of headers will support their learning. There are times where software limits our ability for customization.

4. Visual Hierarchy

- Create a visual hierarchy and organize the elements based on importance to focus learners’ attention on the most critical information first. • Visual Hierarchy in UX: Definition • How Chunking Helps Content Processing?

5. Text

- Based on eyetracking research we start scanning the page from top left. Therefore the best practice is to place the body text on the left as much as possible. If you are designing a page with a diagram or an interactive piece you could experiment with your layout. However, keep in mind the second-best option is placing the text block on the center. • How People Read Online • Text Scanning Patterns: Eyetracking Evidence

6. White Space

- Supporting visual elements should be grouped and positioned to leave ample white space on the page. This will allow our eyes to allow our eyes to roam freely on the page without adding any strain on our working memory. • Proximity Principle in Visual Design • Interaction Design Principles

7. Grids and Rulers

- Grids are essentially the blueprints for your layouts.

- With grids you can:

- Create balanced structure and keep your slides organized

- Establish visual hierarchy to allow learners to easily scan the page

- Design visually appealing slides

1. Branding

- Adhere to your organization’s branding guidelines.

2. Accessibility

- If you are using digital files, make sure your text elements are in the correct hierarchy, have appropriate tags, and are detectable by screen readers.

3. Text as a Visual Element

- Avoid long lines of text and keep the lines about the same length. This is especially important with bulleted lists. Make sure your formatting is consistent throughout, with special attention paid to the line spacing, font, and font size. These elements should also be chosen with accessibility and compatibility in mind.

1. Visual Elements Guide and Checklist for Learning Organizations: A Checklist

Visual elements play a crucial role in adult learning, as they help learners understand complex information quickly and effectively.

This brief guide and checklist will help you manage and optimize the use of photos, illustrations, graphics, diagrams, animations, and videos in your learning materials while adhering to copyright laws and best practices.

A. Copyrights:

- Always use royalty-free or licensed images, graphics, and videos.

- Attribute the source when required.

- Avoid using copyrighted material without permission.

B. Less is more:

- Choose visuals that enhance comprehension rather than distract.

- Use simple and clear visuals to convey the message.

- Avoid clutter and overcrowding in your designs.

C. Plain optimizing:

- Opt for high-contrast color combinations for better readability.

- Use consistent typography and sizing for a cohesive appearance.

- Align elements properly and maintain visual balance.

D. Image resizing vs. optimizing:

- Understand that simply resizing an image in your presentation does not optimize it.

- Use proper image compression tools to reduce file size without compromising quality.

- Ensure images are appropriately sized for the intended medium.

E. Image quality:

- Use high-resolution images to avoid pixelation.

- Select visuals with clear details and legible text.

- Favor vector graphics over raster images when scalability is necessary.

F. Basic image editing skills:

- Learn essential image editing techniques such as cropping, resizing, and adjusting contrast and brightness.

- Use these skills to optimize and enhance your visual elements.

G. Easy-to-use software:

- Utilize user-friendly tools such as Canva, Adobe Spark, or GIMP for image editing and creation.

- Leverage templates and pre-built designs to save time and maintain consistency.

H. Importance of visuals in adult learning:

- Recognize that visuals help adult learners grasp complex information faster.

- Understand that visuals support memory retention and recall.

- Use visuals to break down complex concepts into digestible chunks.

2. Inclusivity

- Challenge stereotypes

- Avoid images that will elicit traumatic responses

- Add meaningful alt text, do the challenging work avoid overused images

3. Photographs

- Any design screen is not complete without graphical elements. Eye-catching graphics can change the mood of the learners and provide them with a different perspective altogether.

- The graphics used in the design should be of high quality and related to the content. Each graphic should have a purpose. Before you add it, ask yourself if it adds anything to the content. If it doesn’t, leave it out.

- Try to use the same style graphics throughout the eLearning/presentation (e.g. cartoon, photographs).

- Avoid using images just for decoration.

- Icons

- A good icon is an image that can help support the text in a course.

- Icon can be recognized by learners immediately

- Icons help leaners easily recall concepts

- Icons help frame an idea

- Follow These Tips to Effectively Use Icons in E-Learning

- A good icon is an image that can help support the text in a course.

- Illustrations

- Illustrations are an excellent way of conveying emotion.

- Scenario or story-based courses are thought to have a higher engagement level for an eLearning course compared to other approaches. Finding the same character images to tell a story or scenario is the biggest challenge. An illustration-based approach offers a lot more flexibility in this respect.

- Icons

Summary: Essential Tips and Design Principles for Graphics

- By following these best practices for creating and using graphics in your learning materials, you will be better positioned to support adult learners in understanding complex information. Remember to keep your graphics simple, consistent, and accessible, and always consider your audience’s needs and cultural sensitivities.

- Choose the appropriate graphic type based on its purpose (e.g., diagrams for processes, charts for data).

- Keep graphics simple and focused on key information.

- Use a limited color palette with contrasting colors for improved readability.

- Maintain consistency in style, color scheme, and typography across all graphics.

- Optimize accessibility by ensuring legible text, using descriptive alternative text, and avoiding color-only meaning.

- Consider cultural sensitivity in symbols, icons, and imagery.

- Test and refine graphics based on user feedback.

Examples and Relevant Links:

- Color contrast: WebAIM Color Contrast Checker – https://webaim.org/resources/contrastchecker/

- Accessibility: W3C Web Accessibility Initiative – https://www.w3.org/WAI

- Graphic creation: Canva – https://www.canva.com/, Adobe Spark https://spark.adobe.com/, GIMP – https://www.gimp.org/

4. Best Practices Guide for Animations at the Alliance

Animations can be a valuable tool in learning materials, helping to clarify complex concepts and increase engagement. However, it is crucial to use animations effectively and responsibly to avoid overwhelming the learner.

This short guide will cover best practices for using animations in learning organizations, taking into consideration cognitive load, working memory, and responsible usage.

A. Use animations purposefully:

- Employ animations to simplify complex concepts, illustrate processes, or highlight relationships between elements.

- Avoid using animations merely for decorative purposes or to add visual flair, as this may distract learners.

B. Balance cognitive load and working memory:

- Limit the number of animations on a single slide or screen to prevent overwhelming the learner’s working memory.

- Be mindful of the cognitive load when using animations; ensure they aid understanding rather than adding unnecessary complexity.

C. Opt for clear and straightforward animations: